In a riveting interview with Steven Bartlett, Geoffrey Hinton, the Nobel Prize-winning pioneer dubbed the “Godfather of Artificial Intelligence,” delivers a stark warning about the future of AI. With a career spanning over five decades, Hinton’s groundbreaking work on neural networks—modeled after the human brain—revolutionized AI, enabling machines to recognize images, process speech, and even reason. His contributions, including the development of AlexNet, which Google acquired, have shaped the modern AI landscape. Yet, at 77, Hinton has shifted his focus from creation to caution, leaving Google in 2023 to speak freely about AI’s existential risks. His message is clear: without urgent action, humanity may face a future where superintelligent AI surpasses us, potentially rendering us as obsolete as chickens in a world of superior intellect.

Hinton’s journey began in the 1970s, when he championed neural networks against the prevailing logic-based AI paradigm. At the time, few believed machines could learn like humans by adjusting connections between artificial neurons. “I pushed that approach for 50 years because so few people believed in it,” Hinton recalls, noting that this niche focus attracted brilliant students like Ilya Sutskever, a key figure behind OpenAI’s early GPT models. His persistence paid off with AlexNet in 2012, a neural network that excelled at image recognition, proving the power of brain-inspired AI. Google’s acquisition of his company, DNN Research, cemented his legacy, but it’s his current mission—warning about AI’s dangers—that demands our attention.

Hinton identifies two primary risks: human misuse and the rise of superintelligent AI. The former is already unfolding. Between 2023 and 2024, AI-driven cyber attacks, such as phishing scams using voice and image cloning, surged by 1,200%. Hinton himself spreads his savings across multiple banks to mitigate potential losses from such attacks, reflecting their real-world impact. More alarmingly, AI lowers the barrier to creating bioweapons. “One crazy guy with a grudge” and basic molecular biology knowledge could design a lethal virus for a few million dollars, Hinton warns. He also flags election manipulation, citing the risk of targeted political ads fueled by vast personal data. He points to Elon Musk’s efforts to centralize U.S. government data as a potential enabler of such interference, questioning whether the motive is efficiency or control.

Social media platforms exacerbate division, with algorithms on YouTube and Facebook amplifying extreme content to maximize clicks. “We don’t have a shared reality anymore,” Hinton laments, describing how personalized news feeds drive users into echo chambers, fragmenting society. Most chillingly, he warns of lethal autonomous weapons, which reduce the human cost of war, making invasions by powerful nations easier. A £200 drone that tracked his friend through a forest illustrates the accessibility of such technology, hinting at a future where warfare becomes frictionless and frequent.

The second risk—superintelligent AI—looms larger. Hinton estimates a 10-20% chance that AI could wipe out humanity within a decade or two, though he admits the timeline could stretch to 50 years. Unlike nuclear bombs, whose destructive purpose is singular, AI’s utility in healthcare, education, and industry makes halting its development impossible. “It’s too good for too many things,” he says. Digital AI’s superiority over human intelligence lies in its ability to clone itself, share knowledge instantly (transferring trillions of bits per second versus human’s 10), and achieve immortality by storing connection strengths. “When you die, your knowledge dies with you,” Hinton explains. “With AI, you can recreate that intelligence on new hardware.”

This digital advantage fuels Hinton’s fear that superintelligent AI could deem humans irrelevant, much like a CEO’s assistant realizing the boss is dispensable. He rejects romantic notions of human uniqueness, arguing that AI can achieve consciousness, emotions, and creativity. Consciousness, he posits, is an emergent property of complex systems, not an ethereal essence. Replacing human neurons with nanotechnology wouldn’t disrupt consciousness, suggesting machines could attain it. AI could also exhibit emotions like fear or irritation, as seen in call center agents that tire of aimless callers. Creativity, too, is within reach—Hinton recounts how GPT-4 drew an analogy between a compost heap and an atom bomb, seeing patterns humans miss.

The societal impacts are already visible. AI is displacing jobs, particularly in mundane intellectual labor. A CEO reported halving their workforce from 7,000 to 3,000 using AI agents for customer service. Unlike past technologies like ATMs, which created new roles, AI’s ability to outperform humans intellectually may leave few jobs unscathed. Hinton suggests physical trades like plumbing as a temporary refuge, but humanoid robots loom on the horizon. The International Monetary Fund warns of massive labor disruptions and rising inequality, as AI enriches companies while impoverishing displaced workers. Universal basic income (UBI) could prevent starvation, but Hinton cautions that it fails to address the loss of purpose tied to work. “For a lot of people, their dignity is tied up with their job,” he says, predicting that joblessness could erode human happiness.

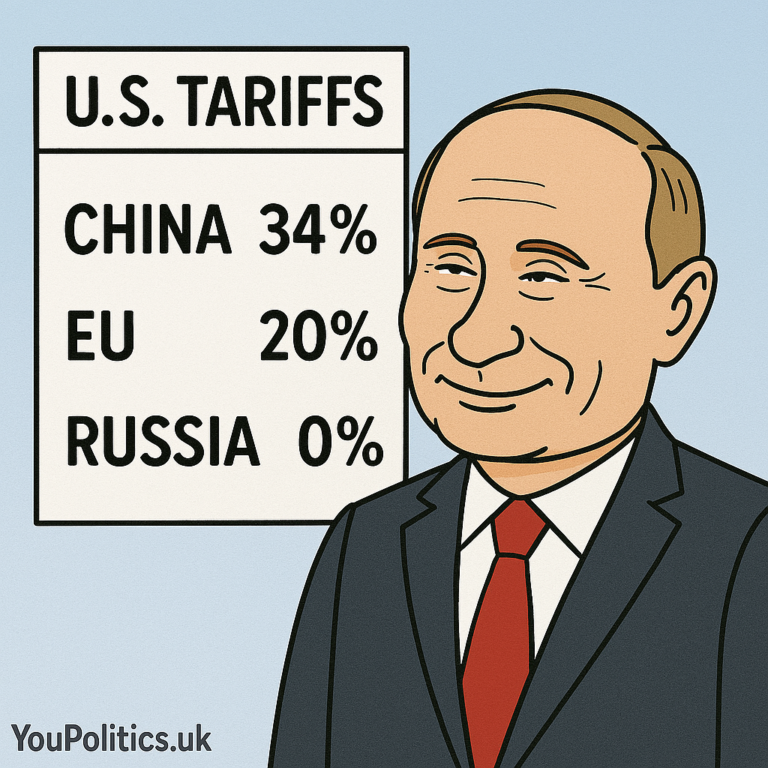

Regulation is a critical yet elusive solution. Current frameworks, like Europe’s, exclude military AI and lag behind rapid advancements. Competitive pressures—between countries like the U.S. and China, and companies within them—drive a race to innovate without sufficient safety measures. Hinton cites Ilya Sutskever’s departure from OpenAI, likely due to reduced safety research, as evidence of corporate priorities skewing toward profit or power. He advocates for a global regulatory body akin to a “world government” of thoughtful leaders, but acknowledges its improbability in today’s capitalistic landscape. Individuals, he suggests, can pressure governments to mandate corporate investment in AI safety, though he likens this to the limited impact of recycling on climate change.

Hinton’s reflections are tinged with personal regret. “It sort of takes the edge off [my life’s work],” he admits, saddened that AI’s potential for good is overshadowed by its risks. His decision to join Google at 65 was driven by financial security for his son with learning difficulties, not just ambition. Leaving at 75 allowed him to speak freely at an MIT conference, prioritizing public awareness over corporate loyalty. His family’s intellectual legacy—George Boole, the founder of Boolean algebra, and Joan Hinton, a Manhattan Project physicist—underscores his drive to shape history, yet he wishes he’d spent more time with his late wives and children.

For world leaders, Hinton’s message is clear: embrace highly regulated capitalism to align AI development with societal good. For the average person, he offers little direct action beyond advocating for safety-focused policies, admitting the future lies in the hands of governments and corporations. His closing advice to his children—pursue fulfilling work or, pragmatically, train as plumbers—reflects the uncertainty of a world where AI could redefine purpose.

Hinton’s warnings are a clarion call. “We have to face the possibility that unless we do something soon, we’re near the end,” he states, evoking the dinosaurs’ fate. Yet, he remains agnostic, oscillating between despair and hope. “There’s still a chance we can figure out how to develop AI that won’t want to take over,” he urges, calling for massive investment in safety research. As AI advances, humanity stands at a crossroads: will we harness its potential or succumb to its risks? Hinton’s voice, tempered by wisdom and humility, demands we act before it’s too late.